<voltar>

NOTE: If you speak portuguese, this page has a companion video:

In Sevilla, there is a cool place called Casa de Pilatos. It is considered a "casa palacio" - a palace house -, which just means it belonged to someone very rich and very interested in architecture.

In February 2023, I was there. I saw it. And although the building was indeed very pretty and full of history, what really captured my attention were its walls. Each was composed of several different tiles that repeated themselves horizontally and vertically, creating an array of shapes that surprised me not only by their diversity but also by their creativity. Some tiles used hard geometrical patterns, others employed floral curves, and many mixed both. I was enamored by their grace and suddenly knew that I needed to know more about them... Much, much more...

As I came to know, this type of ceramic tile is called an azulejo ("ah-zoo-lay-hoe"), and here in Spain their production was elevated into an entire art -- especially in the southern region of Andalusia, where Sevilla is located. In this sense, Casa de Pilatos served almost as a museum: according to Wikipedia, the palace displayed 150 different patterns (!!), making it one of the largest azulejo collections in the world. Here are some of them:

(I was the only one taking pictures of the walls! Can you imagine!?)

To tell you the truth, I became fascinated by azulejos. They allow the artist to paint a whole wall by designing just a small part of it, and then... repeating it. BOOM. It may sound like a special form of laziness, but I would suggest it is actually efficiency, since you are letting the tiles do your work for you. There is a reason why videogames used tiles everywhere in their earlier days: they allow you to do a lot with very little. Like a seed that eventually grows to be a tree, I'm made to ponder: how does a small grain contain such greatness? Surely, each azulejo is a tiny little miracle in and of itself.

Naturally I bought a book on azulejos, one of those tourist books that don't even have the author name on the cover. This one is actually very good, and it provided me with a lot of information on the history of Andalusian azulejos. Now it is my turn to impart this lore onto you.

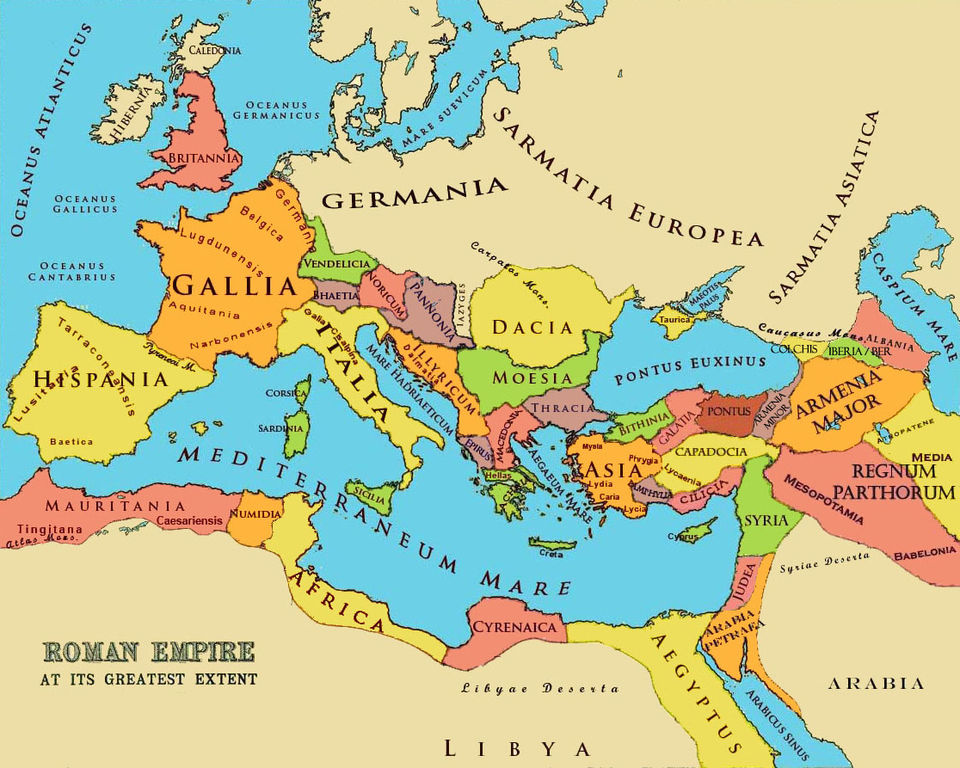

Like many things, the tradition of Spanish tilework can be traced back to the Romans. As you can see on the map below, starting in ~200 BC the Romans controlled various parts of the Iberian peninsula (that's the place where Spain is located), with the region being formally annexed in 19 BC. The official name of the province was "Hispania", which -- surprise surprise -- originated the España/Spain that is still used to this day.

During this time under Roman control, the peninsula was dotted with Roman mosaics: large works of art composed of thousands of small, cubic stones called tessellas (that's where tessellate comes from). These mosaics could be found in both private and public buildings, and they represented everything from festivities to mythological events to scenes of hunting. Hundreds of Roman mosaics have survived to our age, especially those that were displayed on the floors (wall mosaics haven't had so much luck), and indeed we saw one close to Casa de Pilatos in Sevilla:

Because both Roman mosaics and azulejo art use small square elements to compose larger pictures, art historians usually define them as the birth of azulejo art. That may be, but I'm not entirely convinced that they influenced the posterior tradition of Spanish azulejos: the tessellas function essentially as pixels, not as repeating tiles, and they do not contain the patterns characteristic of the previous azulejos that so enamored me in Casa de Pilatos. Indeed, for a more likely ancestor, we need to turn our attention to a later period: the 8th century, when the Iberian peninsula was under control of... the Umayyad Caliphate.

See, at the very beginning of the 8th century, the peninsula was divided into several Visigothic kingdoms that constantly fought against each other. During these battles, Muslim Arab armies from modern-day Morocco were often asked (i.e. bought) for military support, such that they were often crucial in helping one kingdom's victory over another. However, somewhere around 711 AD, a great idea occurred to the Muslims of the Umayyad Caliphate: "what if instead of helping these bickering bastards, we just... conquered them?" And so it was done, and various parts of the Iberian peninsula were brought under Muslim control for a period that lasted almost *800 years*. Let that sink in! This is much, much longer than the Christians that came later and supposedly "reconquered" the peninsula.

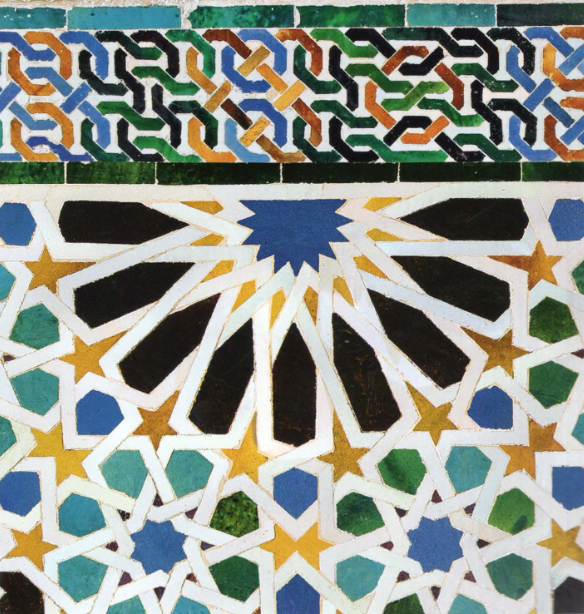

The area ruled by the Muslim Arabs was called Al-Ándalus. Although its capital changed a few times, it was always located in the southern region of the Spain, which today is called "Andalusia" (it's the region with Granada/Cordoba in the image above). Here, Muslim influence was at its strongest, and monuments were frequently decorated with a type of mosaic tilework common in the Muslim world: the so-called الزليج , or zellij. These mosaics were composed of the geometrical patterns so common in Muslim architecture, eschewing colorful curves for straight lines and a limited palette.

(Why is Islamic architecture so obsessed with geometrical patterns? That's a good question. As I understand it, Islamism forbids the representation of religious figures, so Islamic artists naturally have to employ more abstract motifs such as geometrical patterns, Arab calligraphy, and arabesques. I find it very beautiful!)

The thing to pay attention here is that, at this step, the tiles are not square-based. Take the pattern on the right above: each triangle and hexagon is a different tile. Can you see it? There's even a small yellow-ish line separating the shapes, which on modern-day azulejos would be between the squares (apparently this region is called "grout"? I wouldn't know). Imagine how difficult it must be to cut so many tiles and to guarantee that they will fit each other perfectly! It is no wonder that everything was so excessively geometrical: cutting curved stones would be impractical to a fault, specially since an absurdly large quantity of these would be necessary to adorn a large expanse of wall. This must also limit color choice, I'd wager; everything ends up being mostly black, white, blue and orange.

What do you think of these patterns? To be honest, I'm not a particular fan of them; they work, but seem dead in some way. It does not invite you to delve in, does it?

Eventually, Christian kingdoms started fighting against the Islamic states with the goal of "expelling heathens and restoring Christiandom in the name of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ" (nevermind that these Christian kingdoms had little to do with the Visigothic lineages, and that the Islamic ruled the peninsula for far longer than the Visigoths had!). This was the so-called Reconquista ("reconquest"), and it ended with the Christian kingdoms conquering the city of Granada in 1492. At this point, Al-Ándalus was no more.

The zellij tradition was transformed: wealthy Christians, specially in Andalusia, were fascinated with the newly-conquered Muslim architecture and decided to build their palaces in this style. And who better to build them than the Muslims themselves? The assigned artisans were the so-called "mudéjares": Muslims that remained in the peninsula despite Christian control ("mudéjar" comes from the Arab word دجّن, that means "tamed"). The architectural style that ensued was called Mudéjar architecture, with Casa de Pilatos being a prime example: its building started in 1483, just a few years before Al-Ándalus fell for real, and was commissioned by a nobleman called Pedro Enríquez de Quiñones (who supposedly died 10 years later when returning from the Granada War!). The important thing to note here is that a ton of Spanish nobles were requesting Mudéjar buildings, and the demand far surpassed the supply, specially since the Muslim population (who held this tradition) was declining. If Mudéjar architecture was going to be so widespread, it needed to be easier, especially with regards to the puzzle-like zellijs.

Enter azulejos.

More specifically, enter the wave of azulejos renascentistas (Renaissance tilework). These are the square tiles that we all know and love, and as you can imagine, they are much faster to produce than their zellij counterparts due to their standardized shapes. Although the flexibility in tile format is lost (every tile is the same shape, after all), another is gained: curves are much easier to make, which opens up the way for a proliferation of circles, flowers, and curved surfaces in general (themselves already highly prevalent in Islamic architecture, vide the arabesques).

For some reason -- I guess because of the paints used --, most of the tiles maintain the same palette: specific shades of green, blue and yellow, alongside basic black and white. Although restrictive, I do think it helps to produce a cohesive look overall: you may combine different patterns in the same wall, but since they use the same palette, they do not conflict with each other.

By the way, a curious question here is: how are these azulejos painted? If you know anything about ceramic (I didn't), the usual scheme to paint a pottery of some sort is that you have to take the clay, shape it, paint it, and then bake it. This works great if you want to coat the piece with a basic tincture, but things quickly get messy when you try to mix colors. If you use two different paints to color a tile, when you bake them the glazes are going to liquefy and then mix, leaving you with a result that looks like this:

Not exactly what you wanted!

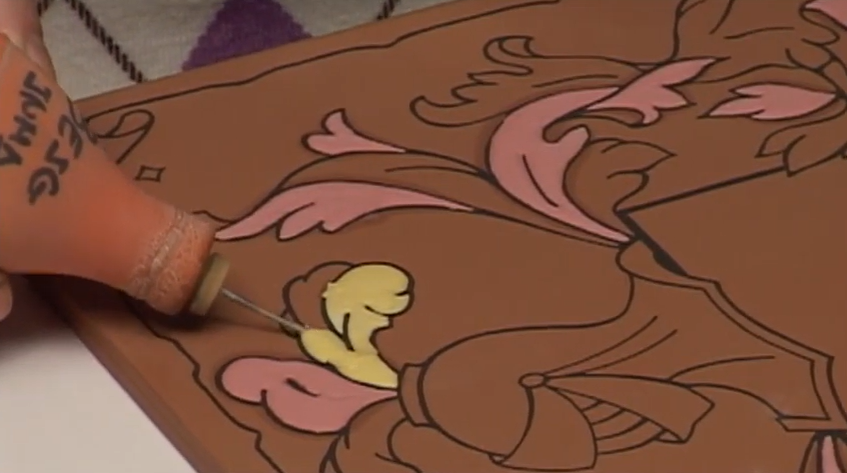

So you need to use some other technique. The oldest one used is called cuerda seca (literally "dry rope"), and it employs a mix of manganese carbonate and grease to create a certain "separator tincture" that looks exactly like black paint. Then, the artisans use this tincture to draw the "lineart" in the tile, which is basically the borders between regions of distinct colors; each region is painted with the colored glaze tinctures, and then the tile is baked. However, the colors don't mix like in the photo above -- what happens is that the "separator tincture" is apolar, so it prevents the colored glazes from mixing with each other! Moreover, the tincture burns up during baking, revealing the tile base under the painting and making the lines have the same grainy texture as the separation between the tiles themselves.

The technique is called "dry rope" because back then, they'd use dry rope to stand in the separations themselves (I couldn't find any more information as to why did they use dry rope specifically). If you're curious, there are tons of videos on YouTube teaching how to make cuerda seca tiles!

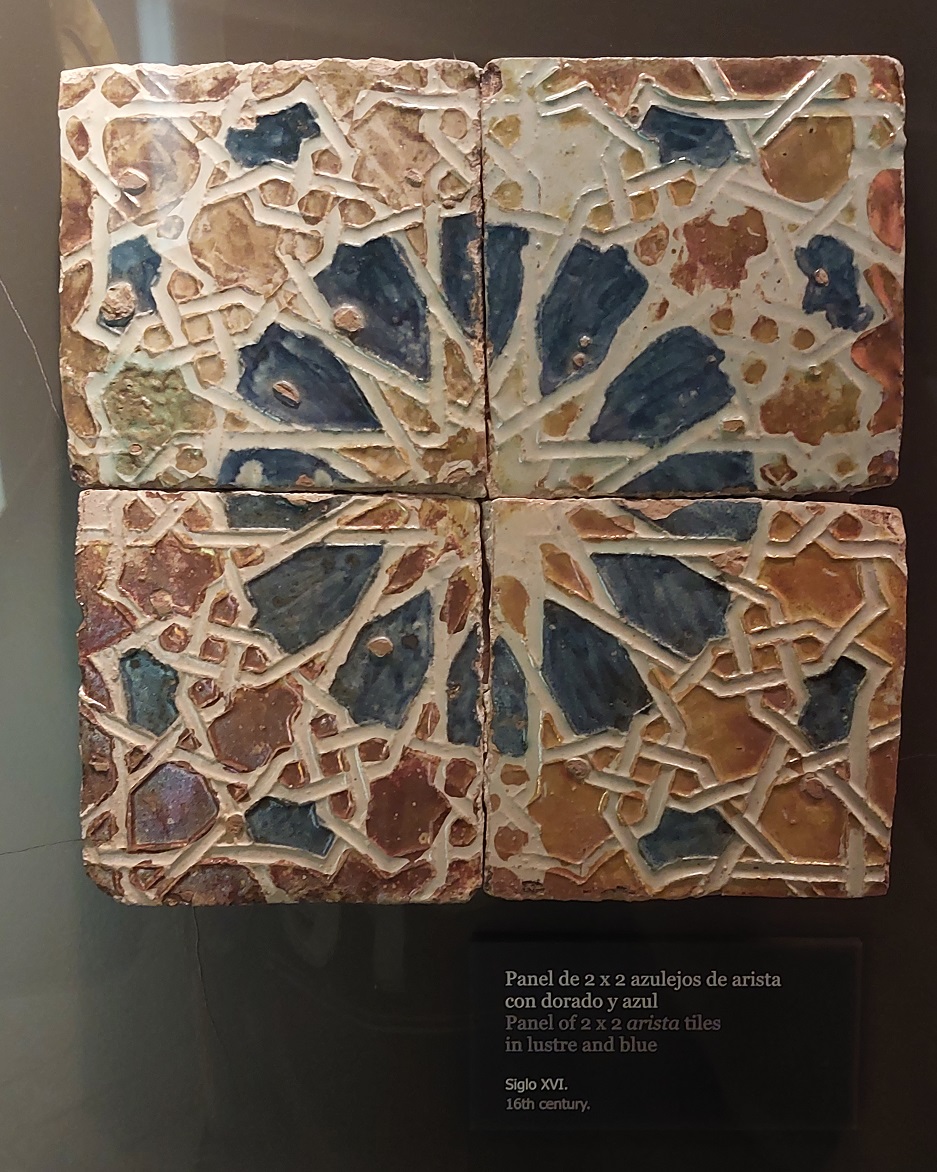

The other, later technique to paint azulejos is called cuenca ("basin", "socket") or arista ("edge", "corner"). In this technique, a wooden mold is pressed unto the raw clay, making a high relief drawing in which distinct regions of color are separated by an "elevated lineart". This solves the color mixing problem because, as you can imagine, the different glazes are not touching each other -- the walls of the "sockets" inventively separate the colors without any additional chemical. This can be clearly seen in the image below.

The arista technique makes it faster to produce a large number of azulejos if you have a mold, since you don't even have to draw the lineart, but for smaller-scale operations, the cuerda seca technique still seems to be preferred -- indeed, I couldn't find any videos on how to make azulejos de arista on YouTube! Bummer. As you might've guessed, it's easy to identify the technique used to paint an azulejo by looking at the lines separating different colors: if they are made of the same material as the tile base, then it's an azulejo de cuerda seca, but if they have a higher elevation than the rest of the tile, it's an azulejo de arista.

Aside: I love when the tiles are imperfect. Look at it this way: in theory, every tile is an anonymous entity, useful not by itself but only as part of a greater whole. Who would buy a single of these pattern tiles, after all? People buy them in bulk; the individual tile does not matter in the slightest, it is perfectly replaceable. However, when you really get close to them, you start noticing inconsistencies: places where the line from a tile loses its way and does not perfectly connect to its brother in the adjacent tile. Places where the color changes from a tile to another, as if they had different moods. These imperfections aren't common today, in our industrial age: machines don't make mistakes, and when they do, the mistakes are thrown away. But in Casa de Pilatos for example you can basically only see mistakes -- no transition is perfect. This is a stark reminder that these were made by human hands, such as mine and yours. They bring me back to the moment that the tile was made. Did the artisan get distracted? Was the mold getting used up? Did the tiles simply move inside the kiln? Even though the tiles might not open up their secrets, they have much to say. Each a moment, baked upon eternity.

...and back to history. Due to the particular historical happenings of the time, the 16th century saw the birth of a new kind of azulejo style, different from the renascentista that we've been talking about. You see, most of the azulejo action was centered around Sevilla (the capital of Andalusia), and the city was actually going through a very curious time: Spain had "discovered" a wonderful place called "America", which had -- would you believe it! -- tons of gold, crops, and exotic materials of all kinds. "It's Free Real Estate" said the Spanish Crown, who then sent thousands of ships to make the most out of this divine opportunity. To enforce utmost control over this first-ever ultramarine empire (and therefore guarantee that everyone would pay their taxes), the royals decided that every ship coming from America would be forced to dock in Spain at the same place: an easy-to-monitor bottleneck in the Guadalquivir River called the "India Port", which happened to be in... Sevilla.

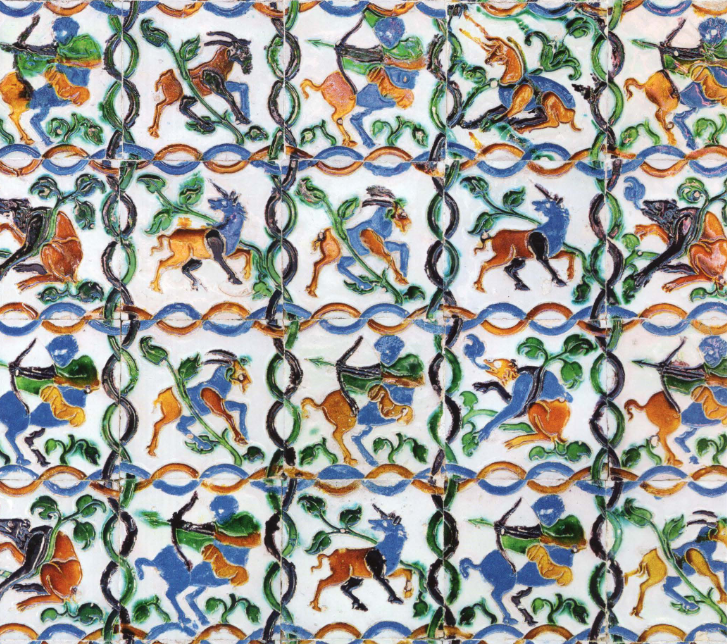

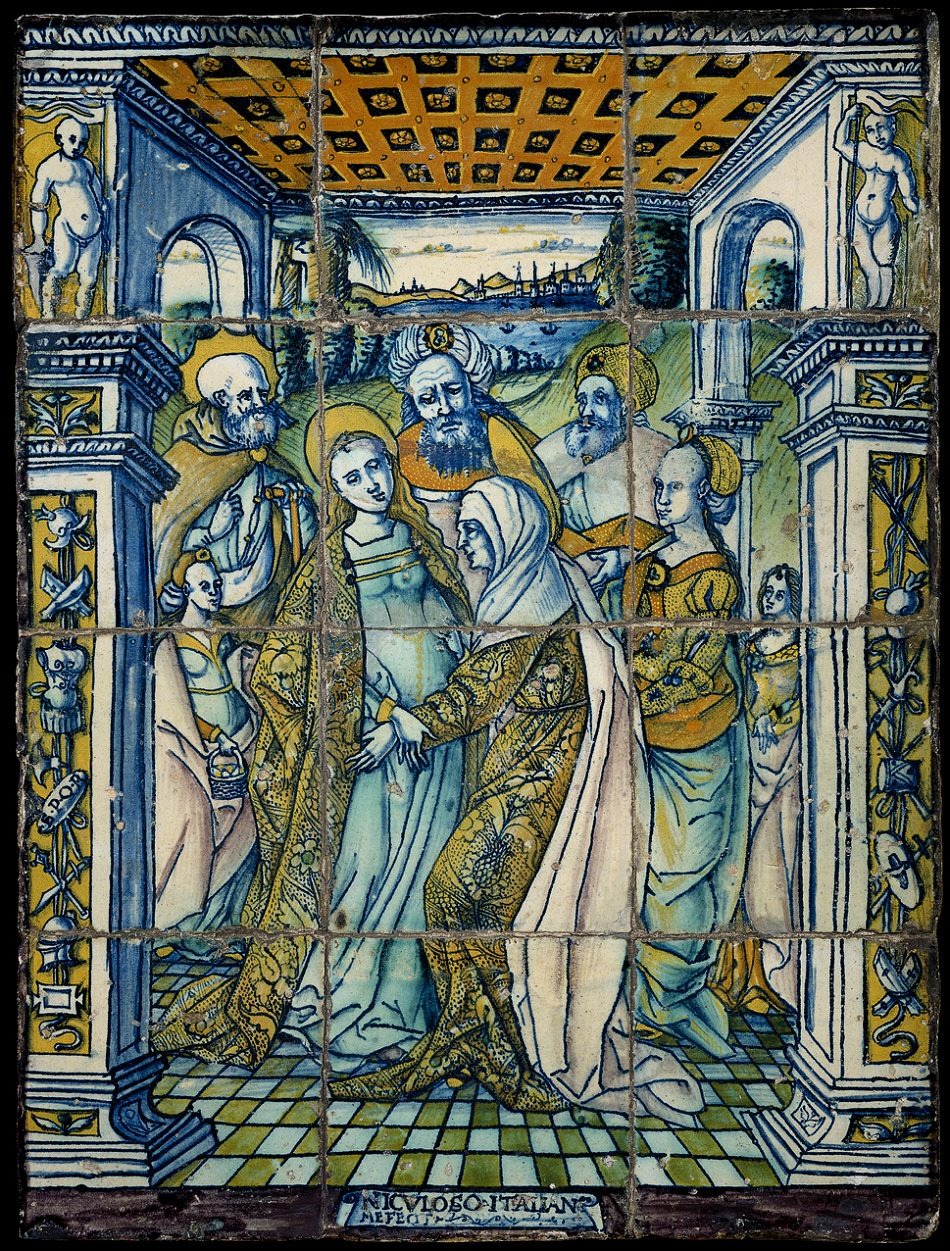

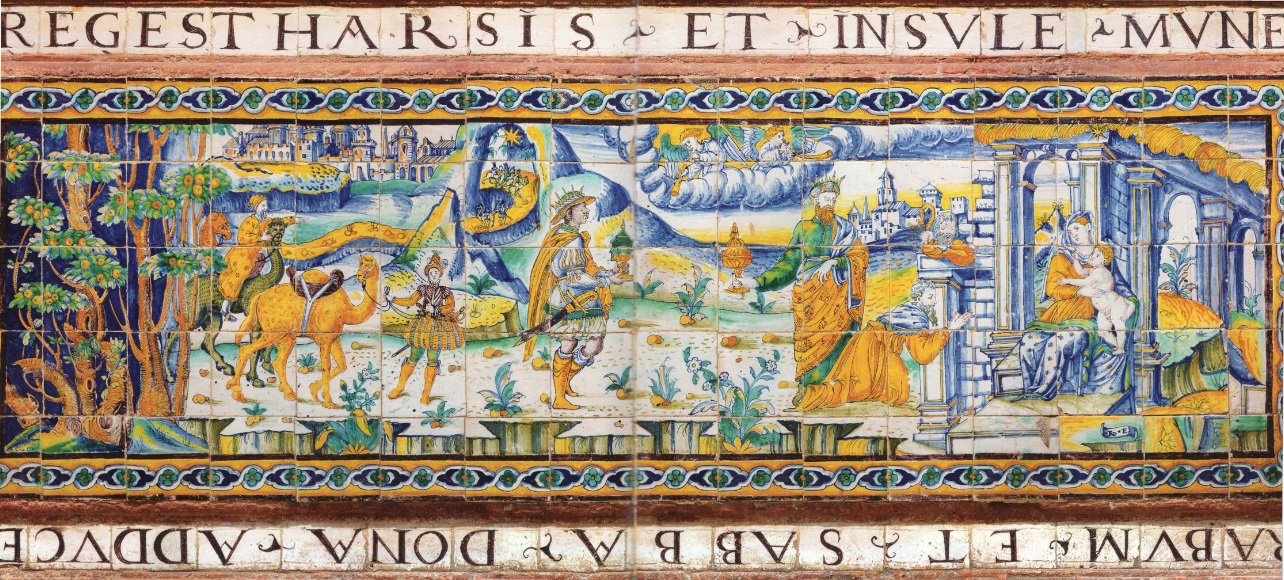

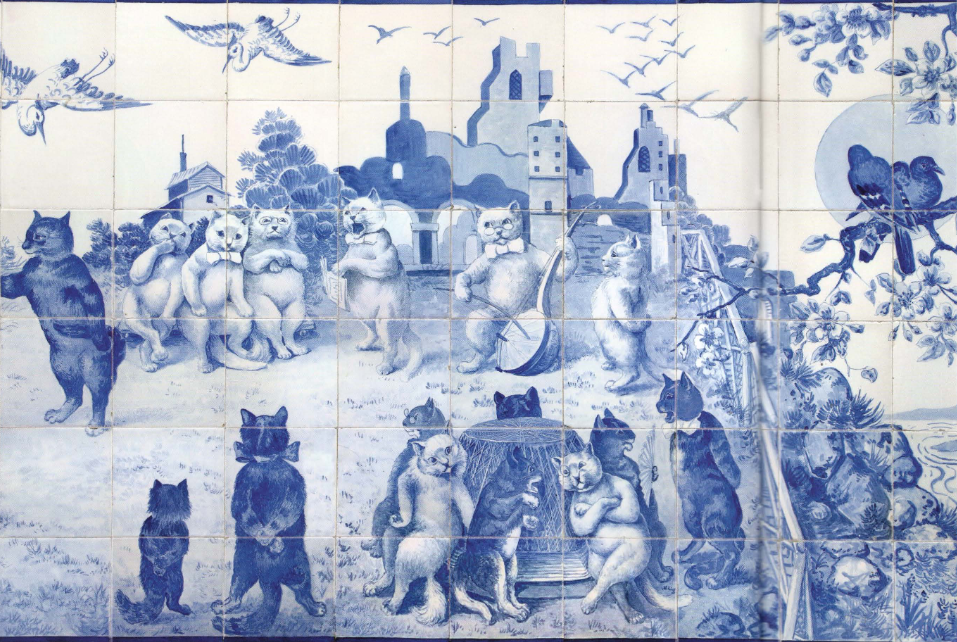

So rather unexpectedly, Sevilla went from "that place the Arabs liked so much" to "nexus of the New World Order". Good for them, I guess! This meant a lot of merchants were coming to the city, bringing their traditions with them: Napolitan, Flemish, Venetian, and many more. The ensuing cultural zeitgeist gave birth to a new wave of tilework, based on ceramic painting techniques from Italy: the so-called azulejos pintados ("painted tiles"). "Wait, weren't tiles always painted?" you may be wondering. And you'd be right, they sorta were!, but now they contain paintings. Look:

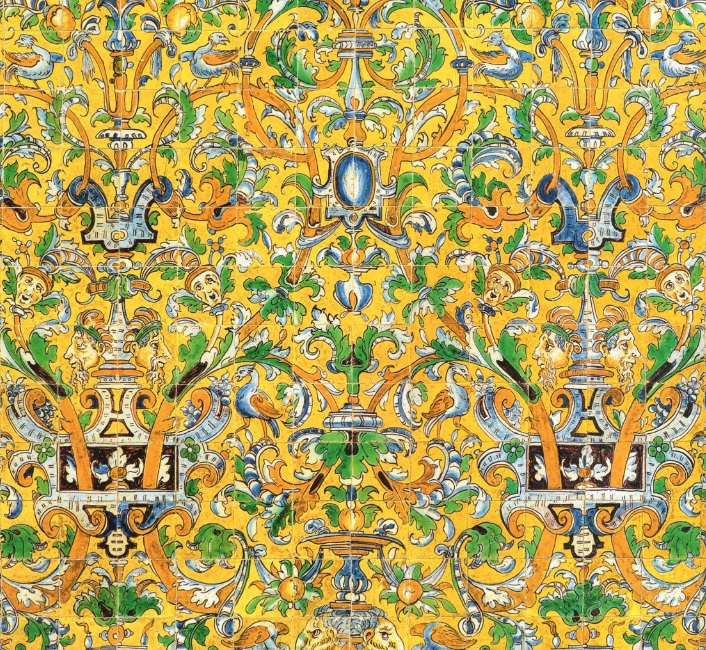

As you can see, the geometrical patterns give way for much more representative depictions, usually of Renaissance themes or Christian mythology. The tiles are still there of course, but they are somewhat incidental to the whole scheme, serving basically as a medium through which the artist can do a mural painting without making a fresco. In conclusion, we have come full circle: the azulejos pintados now function exactly as the Roman mosaics did 1500 years before -- although the tessellas have become much bigger!. The patterns have not went completely away though, as we can see from these beautiful walls in the Renaissance Alcázar de Sevilla, built in 1543:

Such patterns have become even bigger, sometimes taking up multiple tiles to reveal their grander plan. It is as if the wall were composed of giant tiles, each composed of smaller individual ones.

(As an aside, let us dedicate some attention to the curious little critters that dot the walls of the Sala de las Bóvedas of the Real Alcázar. My book simply calls them "fantastic animals", although I'm sure they're not only fantastic but also kind and gentle.)

(I also love this one from the Mosque of Córdoba. See if you can spot where two tiles were switched, God knows why:)

The popularity of painted tiles eventually waned, due to the Spanish empire's economic instability and military decadence in the 17th and 18th centuries. It certainly didn't help that King Phillip III, in 1609, ordered the expulsion of every morisco (Muslims who converted to Christianism) from Spain: since a lot of the labor in azulejo production was provided by this sector of the populace (unsurprisingly), the industry took a hard blow. Because at this time the Baroque artstyle was spreading across Europe, the azulejos painted in this era were called azulejos barrocos. Stylistically they are quite similar to the azulejos pintados that preceded them, but thematically they differed themselves by eschewing the high and mighty for more worldly subjects. Less Jesus and more people hunting, less Saints and more people going around their business downtown. Less God and more... women playing with animals?

This one is a cool panoramic view of the Alameda de Hércules in Sevilla:

This one curiously depicts a Renaissance Emo Kid:

(Pay no attention to the drape-spitting amoeba at the top of this last one)

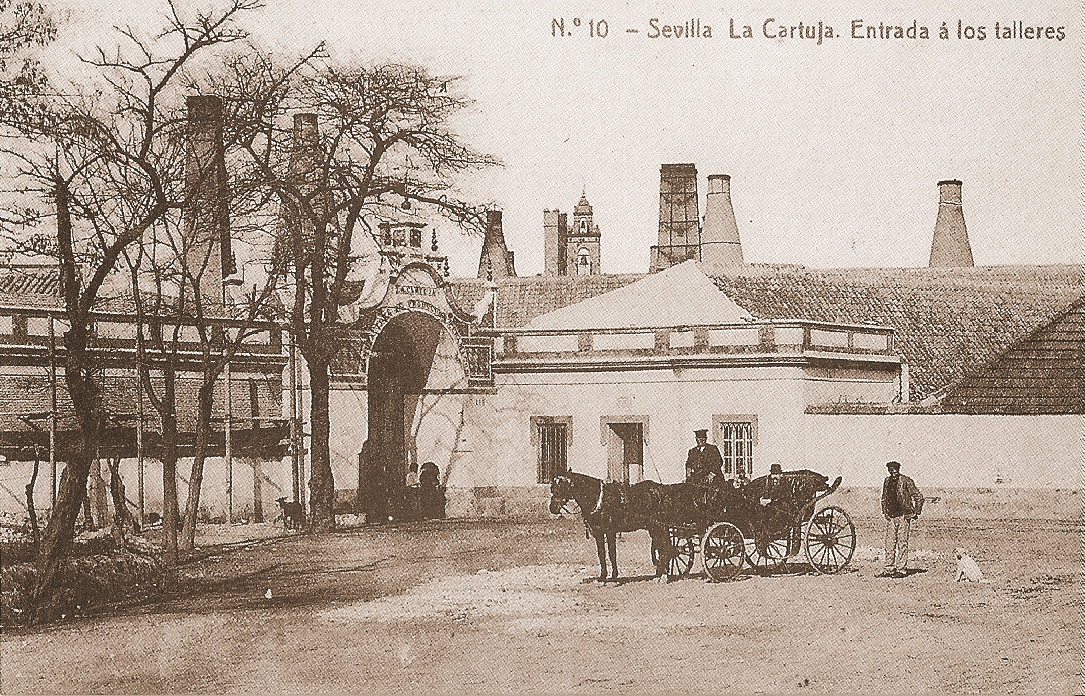

Then, in the 19th century, things changed yet again. A well-respected English merchant called Richard Pickman caught wind of the fact that Spain had a lot of interest in ceramic, which he found very interesting since his job was to sell ceramics and glassware in several British cities. In an attempt to exploit this opportunity, Richard sent his son William in 1810 to establish trade in Andalusía. Sadly, William died 12 years later without much success, but his half-brother had entirely different luck: Charles Pickman -- or as he is called in Spain, Carlos Pickman -- moved to Sevilla in the same year as the death of his half-brother, and not only established a thriving business there, but actually built up a business so large that he founded his own tile factory in 1842: the famous Factory of Pickman La Cartuja.

This ceramic factory became one of the best well-known in Europe, so much so that in 1871 it became the primary tilework supplier of the Spanish Royal family! Not only that, but Charles Pickman himself ended up receiving the title of Marquis, becoming a noble of his own right! Very curious.

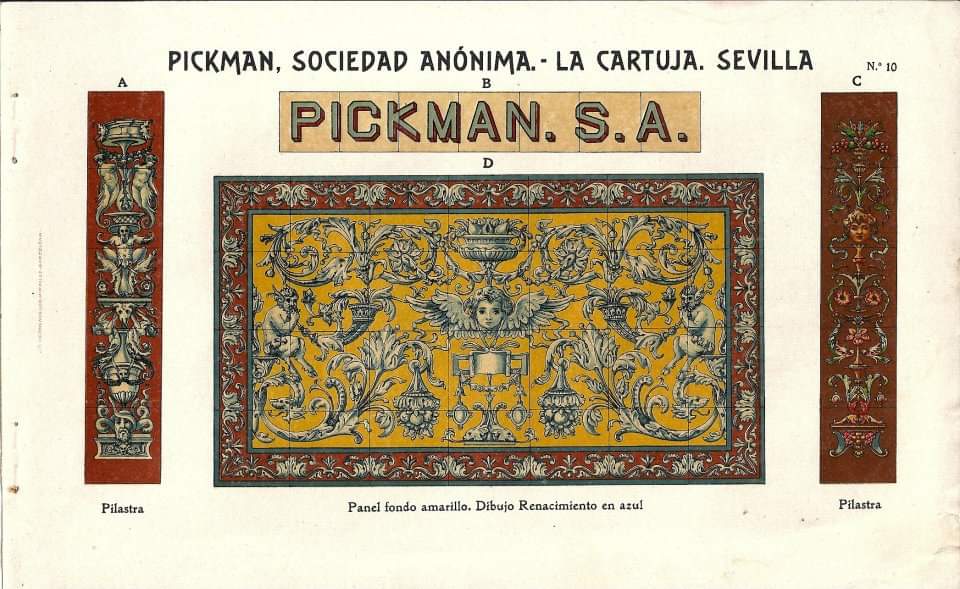

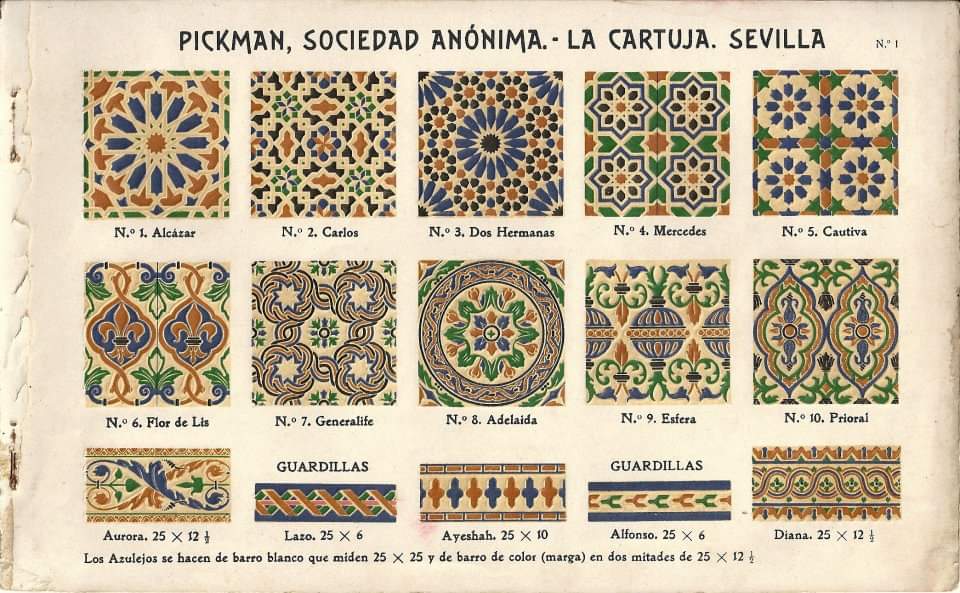

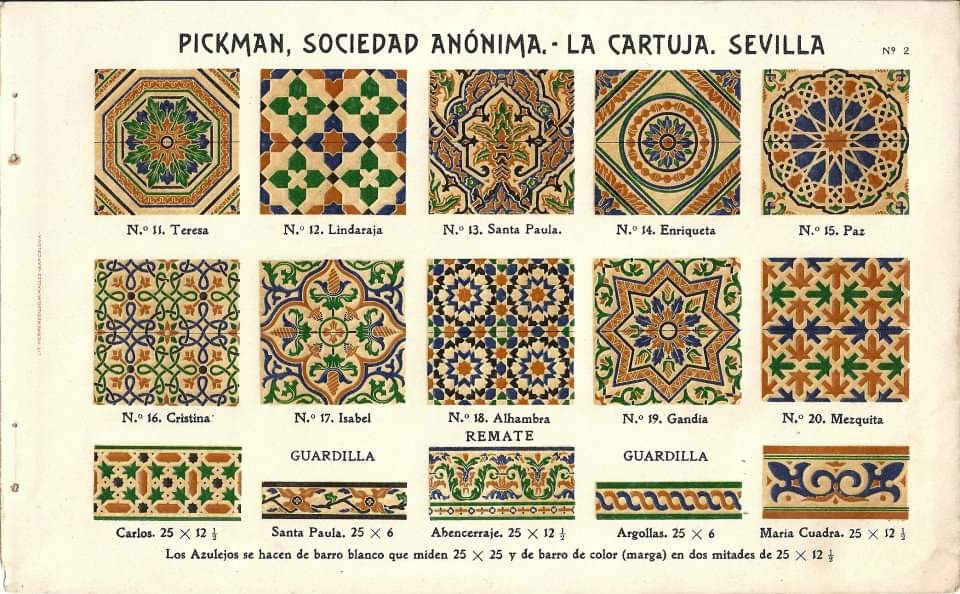

Here is the earliest catalog we have of the factory's output, dated to 1896:

As we can see, full of the patterns that we all know and love. My favorite is Nº 17, although Nº 20's Dance Dance Revolution comes a close second. Which would you like on your house?

It should be said that this revival of the pattern-based single-tile azulejo feeded unto the broader "historicista" movement that colored Spain's 19th century. In the interest of powering up nationalist ideals, this movement highlighted traditional Spanish art forms, with pattern-based Andalusian tilework among them. As an example, take a look at these azulejos made for the Cropáni Palace in Málaga that just so happen to have the same intoxicating yellows as the ones in the Sala de las Bóvedas of the Real Alcázar, built 400 years before:

Similarly, take a look at the façade from the Casa de los Mensaque, built in 1900:

Or these ornaments from the Mensalves Palace:

So pattern-based, palette-restricted azulejos had been revived alright. But actually though, my favorite from this period is this one from the Casa de los Mensaque:

The artist was sure having fun!

Another cool example that deserves mention is the Plaza de España. In 1929, Sevilla hosted the Exposición Iberoamericana ("Ibero-american Exposition"), a world fair which had the express purposes of both (1) improving diplomatic relations between Spain and its former colonies in America, and (2) bolstering tourism in Sevilla. Each invited country would have a Pavilion in an enormous park, where they could erect a building in homage to their cultural development and architectural history. Here is the poster:

Spain, being the host, constructed the largest and most expensive building of all: an open square called "Plaza de España".

Since buildings were made to show off the architectural particularities of each country, of course that Spain resorted to a traditional medium that developed there: azulejos. Indeed, azulejos became the primary ornamentation of this large plaza, such that it is hard to take a photo in it that does not contain a single azulejo. They dot the roofs, pavements and façades.

The most famous use of azulejos is, however, in the province benches. See, there are 48 benched spread around the Plaza, each dedicated to a different Spanish province and illustrating a relevant scene of this province's history. And of course, everything is made of azulejos, in a mixture of pattern and painting.

Sometimes the benches even have queues! You see, tradition demands that every Spanish tourist travelling to Sevilla must take a photo sitting in their province's bench. There isn't a bench for Brazil of course, so I just took a photo in this uncomfortable bench instead.

...And that's really all there is to say on the matter!